Colours of the Forest

Naturally dyed cotton yarns created by Mehinaku women in Kaupüna, following workshops led by Maria Fernanda Paes de Barros and natural dye researcher Maibe Maroccolo.

Xingu: Indigenous Reflections in Contemporary Design

Morning unfolds slowly in the village of Kaupüna, home to the Mehinaku, one of the sixteen Indigenous groups in the Xingu Indigenous Territory, located in Mato Grosso, Brazil. The cool red earth is marked by children's dances from the day before, while smoke curls from fires where beiju — a thin, round bread made from cassava — is being prepared. Its scent mingles with the sweetness of crushed urucum seeds used for body paint — a plant that also carries protective and ritual value. Hammocks sway in the shade, woven from buriti palm fibres that catch the early light. This sacred tree provides not only weaving fibres, but also nourishment, shade, and spiritual significance — anchoring many of the Mehinaku's daily and ceremonial practices.

Today, the Mehinaku number around 500 people. They live in harmony with their rivers and forests, carrying forward rituals, stories, and craftsmanship that nourish both memory and community. For them, craft is inseparable from life; a mat, a basket, a bench, or a hammock is never just an object — it is an extension of kinship, territory, and cosmology.

Every gesture carries knowledge: the right moment to harvest the buriti palm, the pressure of fibres twisted on a thigh, and the patient drying of wood before carving. These skills represent threads of connection — among generations, between bodies and landscapes, and between the visible and the unseen.

However, it is precisely in the face of such a scene that the risk of misinterpretation arises. The beauty of the Xingu — its sounds, colours, and gestures — can easily be romanticised or exoticised by outside observers. For centuries, design and art history have extracted Indigenous practices as aesthetic inspiration, cataloguing them as artefacts or idealising them as untouched traditions. In both instances, Indigenous peoples are denied their current existence and often portrayed as either frozen in the past or transformed into distant, symbolic figures.

Yet the Mehinaku live fully in the present. Their society is sustained not only by crafts and rituals but also by political and economic systems that ensure autonomy in the Upper Xingu. Economically, they fluidly navigate between subsistence practices, such as fishing, farming, and weaving, and broader exchanges, selling crafts or engaging in collaborations that generate income while enhancing cultural pride.

Mehinaku life, therefore, cannot be reduced to mere "tradition" or aesthetics. It is a living system of knowledge: a dynamic interplay of governance, economy, and culture, rooted in territory yet responsive to the world beyond.

Tracing Stories

Among those who have come to learn from and collaborate with the Mehinaku is designer Maria Fernanda Paes de Barros, founder of the studio Yankatu. Drawn by a deep respect for ancestral knowledge, her work seeks to connect design with storytelling, memory, and reciprocity.

Yankatu is more than just a design studio; it serves as a platform for dialogue and connection. It was established out of a desire to listen and trace the subtle threads that weave together people, places, and traditions. In its early years, every piece of furniture she created was accompanied by a small notebook called "alma" (soul). This booklet contained reflections on the artisan, the inspiration behind the piece, and the cultural roots tied to the object. Some pages were intentionally left blank, inviting new owners to continue the story in their own way—transforming each item into not just a possession, but a shared narrative.

In 2019, Maria Fernanda met Kulikyrda Mehinaku at SP-Arte in São Paulo, sparking a meaningful connection centered on design and craftsmanship. Kulikyrda Mehinaku is a respected cultural leader and artist who plays a vital role in preserving and sharing the traditions of his people.

This initial exchange led to an invitation for Maria Fernanda to visit Kulikyrda’s village, Kaupüna, where she witnessed a women's ritual that underscored the importance of reciprocity in collaboration. In Kaupüna, she encountered a vibrant community of artisans and a rich, living system of knowledge.

Kulikyrda’s gesture was more than mere hospitality; it was an act of cultural openness, founded on trust and mutual respect. Together with Stive Mehinaku, an artisan and designer from Kaupüna, Maria Fernanda created the Xingu collection, which features basketry, furniture, and mats.

During her time in Mehinaku territory, Maria Fernanda learned from the women who weave with buriti palm. She realized that their craft serves as a bridge between memory and daily life, as well as between ancestral heritage and contemporary needs.

Colours of the Forest

As the exchange between the Mehinaku women and designer Maria Fernanda Paes de Barros deepened, new dimensions began to emerge — not only in form, but also in colour.

The Mehinaku already had a deep knowledge of natural pigments extracted from plants such as saffron, annatto, and genipap, traditionally used to dye buriti fibres and threads. Maria Fernanda's visit did not introduce this wisdom; instead, it opened a new chapter focused on exploring the untapped potential of other forest elements — bark, leaves, and roots — as sources of natural dye.

For Maria Fernanda, bringing cotton yarns dyed with natural pigments was more than a symbolic gesture — it was an invitation to experiment and collaborate. These naturally dyed yarns not only hinted at new aesthetic possibilities but also offered a practical path towards generating greater economic and creative autonomy within the community. When she arrived in Kaupüna, the vivid colours did more than delight the artisans’ eyes — they stirred curiosity and reflection, prompting the women to re-examine the colours already held within their environment. Surrounded by a landscape rich in tonal variation, they began to ask: what other hues might the forest quietly contain, waiting to be revealed?

To support this exploration, Maria Fernanda invited Maibe Maroccolo — founder of Mattricaria and a specialist in botanical dyes derived from Brazilian biomes — to first develop the colours in her studio and then lead workshops in the village, sharing her findings. Together, they collected natural elements from the environment and transformed them into colour through intuitive practices such as boiling and soaking.

Among the sources gathered were the roots of trees traditionally used to build the community's ocas (houses) — including pindaíba, copaíba, embira, and cinnamon. The result was a palette born of the forest — twelve shades created in harmony with the earth. This renewed exploration of natural dyeing strengthened their connection to the forest, expanded ancestral knowledge, and became an act of cultural affirmation — a way to listen more attentively to the quiet offerings of the land.

The Exhibition as Dialogue

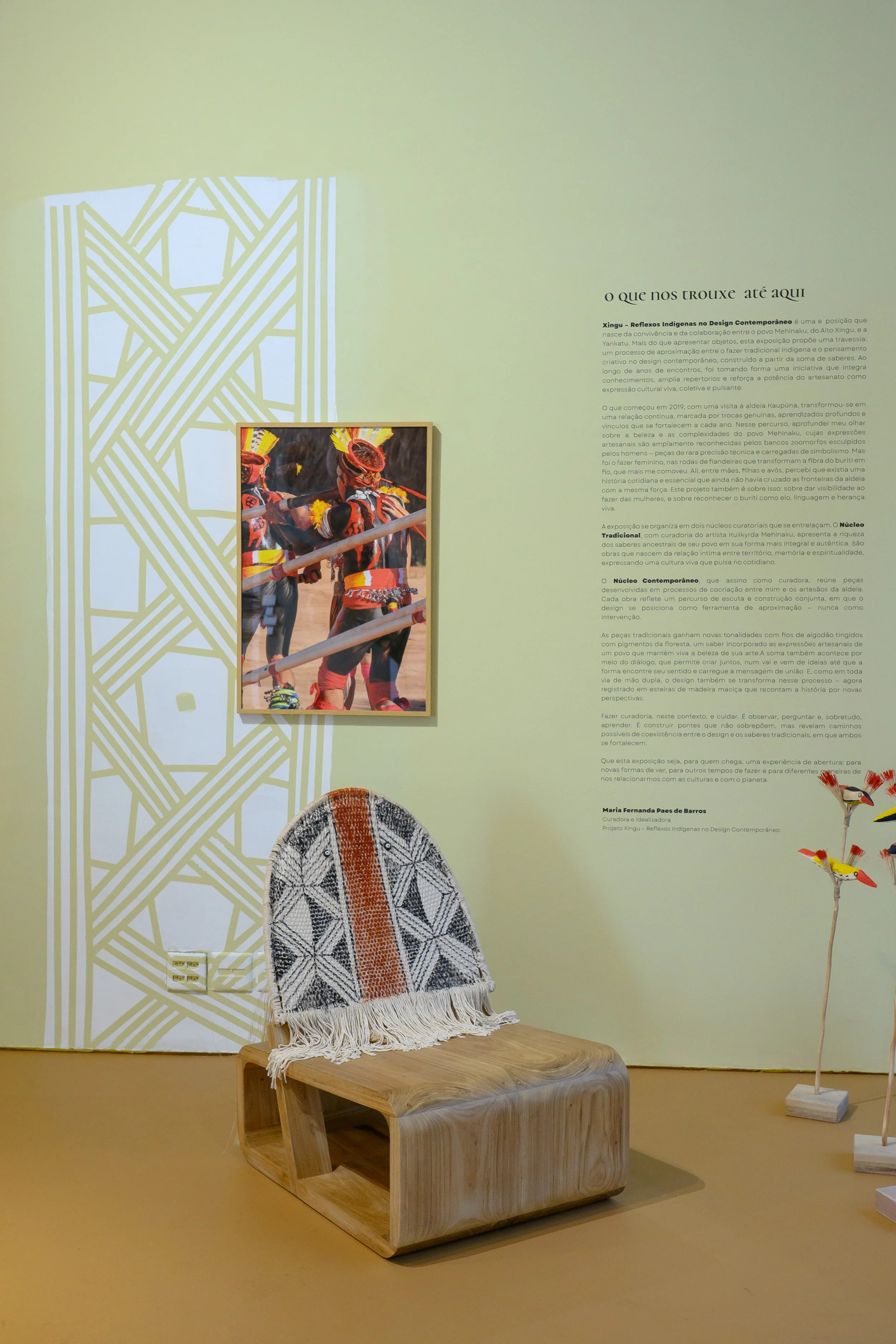

The knowledge shared, the materials transformed, and the stories woven between the Mehinaku and Maria Fernanda Paes de Barros take tangible form in the exhibition Xingu: Indigenous Reflections in Contemporary Design.

At the heart of the show, held at Museu A CASA in São Paulo, are the works of the Mehinaku people — hammocks that sway like forest canopies, mats that reflect the patterns of earth and water, and baskets and benches shaped by memory and ritual.

In harmony with these traditional pieces, new works emerge from the vibrant dialogue between the Mehinaku and Maria Fernanda, blurring the lines between “traditional” and “contemporary.”

The exhibition offers more than objects. It proposes another way of thinking about design — as a practice of care and connection, where each gesture sustains the delicate balance between people and place.

Featured

Mehinaku

Maria Fernanda Paes de Barros

Maibe Maroccolo

Photography

Courtesy of @yankatu

Photography by Lucas Rosin

Exhibition Photography ZZ Foto e Vídeo

Xingu: Indigenous Reflections in Contemporary Design

Realised through the Federal Law for Cultural Incentives (Lei Rouanet), Brazil

Support: Garland Magazine (@garlandmagazine), The Dealers (@_thedealers)

Partnership: Museu A CASA (@museuacasa)

Sponsorship: Sherwin-Williams Brasil (@sherwinwilliamsbr)

Realisation: Yankatu (@yankatu), Ministry of Culture – Brazil (@minc)

Concept, General Coordination & Curatorship: Maria Fernanda Paes de Barros @yankatu

Curatorship: Kulikyrda Mehinaku

Dye Research: Maibe Maroccolo @mattricaria

Executive Production: Angelo Miguel Lima @angelomigue

Local Production: Stive Mehinaku @stivemehinako

Visual Identity & Graphic Design: Maria Helena Emediato @lenaemediato

Texts: Angelo Miguel Lima @angelomigue

Editing & Proofreading: Fernanda Prates de Mendonça

Translation: Maria Fernanda Paes de Barros @yankatu

Exhibition Design: Daniela Karam Vieira @danielakaram

Installation: Rosemi Amorim da Silva @mirosmi

Filmmaking: Victor Affaro @victoraffaro

Video Editing: Fábio Mota @fabiomotaeditor & Rita Basile @basileproducoes

Subtitles, Sign Language & Audio description (video): Temporal Produtora de Acessibilidade e Comunicação

Photography: Lucas Rosin @lucasrosin

Photography Assistant: Carolina Magliari @_carolmagliari

Exhibition

Xingu: Indigenous Reflections in Contemporary Design

Exhibition venue: Museu A CASA, São Paulo, Brazil

Dates: 25 May – 20 October 2024

Words Nina Zulian